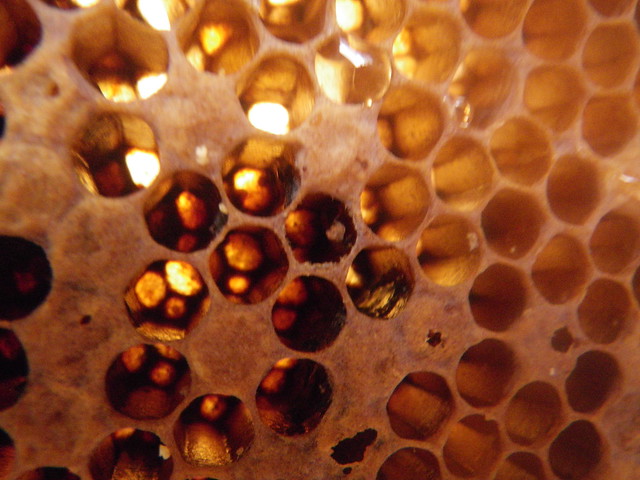

What a mouse in a hive looks like

Once a mouse enters a hive they typically chew out the bottom corner of a few frames to make space. They will then bring in nest material. This is a view from the bottom of the box:

You will probably see evidence of the nest on the bottom board as well.

If you are using a screened bottom board, there is a good chance you can determine if you have a mouse just by looking at the tray under the screen for mouse droppings and fallen nest material.

It's said that mice will often move out as it starts to warm up and the bees become more active. If not, the bees can attack the mouse and you may find the remains (possibly propolized) within the hive.

Aside from the damage to comb, mice are also problematic in the pungent stench of urine that they leave behind in the hive.

Evidence a shrew has been around the hive

Photo by: minipixel / CC: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License

Photo by: minipixel / CC: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License

Shrew's don't nest in the hive, but they do leave behind signs of their visit. You may find droppings that are slightly different than those of mice. There will also be bee carcasses. Shrews eat the bee innards and leave behind a hollow exoskeleton. Most often they get at the innards via removing the head of the bee.

If you do successfully exclude shrews from your hive, you may still find these decapitated dead bees outside the hive. It seems like they will feed on either the dead bees taken out by the undertaker bees, or those bees that leave the hive to die. Shrews are small but they need to eat frequently, over the course of a winter they can take a significant toll on the bee population.

Shrew and Mouse excluders

Generally the standard wooden entrance reducer is not sufficient for excluding mice, there are many stories of the wood being chewed away to enlarge the opening.

For a few years I've seen good results from both simply adding nails to standard entrance reducers and cutting myself thicker wooden entrance reducers from 1.5" wide wood. Was I just lucky?

It's very popular to make or purchase metal excluders with holes drilled into them.

Photo by: Tie Guy II / CC: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License

Photo by: Tie Guy II / CC: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike License

The use of hardware cloth as a mouse excluder is not uncommon either.

Size of entrance required to exclude mice and shrews

The openings beekeepers use for a mouse excluder are sized between 1/4" (6.35mm) and 1/2" (12.7mm), with commercial products typically using a 3/8" (9.25mm) diameter circle.

There's a fine line between leaving enough space for adequate ventillation, allowing bees to remove the dead, and to bring pollen in during the early spring, while still securely preventing mice from entering. There's lots of debate as to whether a 1/2" gap is sufficient to keep the mice out versus 1/4" making it too difficult for the bees to do everything they want to do.

As far as the 1/2" camp goes, there are some beekeepers who claim to have not had a problem in 40 years. There's also some references from mouse owners using 1/2" mesh cages for adults (but many in the mouse world do seem to cite needing 1/4"). Are their regional differences, like species of mice, as well as how likely it is to find smaller, younger mice at the time of winterizing, your hive?

I haven't found as much info out there about shrews. There is reference online to Fletcher Colpitts, Chief Apiary Inspector of New Brunswick citing the use of both 1/4 and 3/8" spacing for winter and then switching to 1/2" once there is spring pollen. Anecdotally, I can say I am finding beheaded hollowed out bees this year outside, but not inside of the hive in the photo above which is using 1/2" mesh with the vertical opening height made slightly smaller as it overlaps the wood of the hive. I take that to be a positive sign.