1. Why do I want to be an urban beekeeper?

In light of all the recent media attention given to mass bee deaths, there has been a dramatic increase in people getting into urban beekeeping with the hope of saving the bees.

Certainly, the value of bees as pollinators is monumentally important for the web of life on this planet, and this is a very worthy cause to take on. What's important to consider is that we most often hear about honeybees in the media due to their importance in modern industrial agriculture. There are, however, 20 000 different types of bees, many of them facing serious challenges, without a fraction of the people looking out for them that the honeybee has.

If your goal is to save the bees, you may wish to devote your energy towards providing habitat for the other types of wild bees rather than honeybees. In fact, researchers from the university of Sussex have suggested that large numbers of new urban beekeepers populating cities with honeybees could be threatening the health of other types of bees as it leads to increased competition for limited resources.

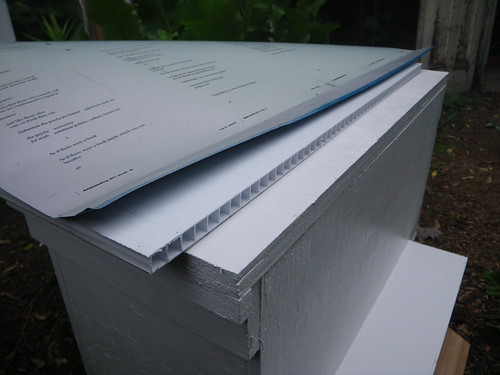

Here's an example of a simple wild bee condo:

Photo by: Joe Thomissen

If you're interest is honey production, the ideal choice in many parts of the world is the honeybee. My understanding is that locally produced honey has about as low an ecological footprint as you can find in a sweetener, so maybe there's room for noble cause cred looking at it from this angle too.

There are, of course, innumerable other reasons to keep bees. Ask yourself what you hope to get out of the experience. This will put you in a better position to find a path into urban beekeeping that best suits your desires.

2. How much time does it take to keep bees?

I always find this question difficult to answer as I am the sort of person who's always trying to spend more time with them. I can say that at minimum, particularly in densely populated urban areas, it's responsible to check your bees for signs of swarming once a week in the spring; a swarm typically waits till some of the new queen larvae they are raising are nine days old before departing. With experience, in the summer and fall it is theoretically possible to get away with a few weeks between checks if your timing is strategic and all is going well with your hives. There are, of course, situations that may arise where a colony needs some attention a few days in a row.

In my mind, time spent looking in the hive is really the tip of the iceberg. Especially in the beginning, getting yourself prepared for your hive checks, both in terms of knowledge and equipment, can take up more of your time than anything else. Proper preparation allows your checks to be as purposeful and efficient as possible and will save you time in the long run.

You will always need to be budgeting a few hours here and there for putting together that extra hive box, sorting out a feeding system you didn't think you would need, figuring out what a weird unexpected behaviour is all about, etc.

If all this sounds daunting, anticipate that one day you will discover a sudden urge to buy flowers for your lovely fuzzy buzzing ladies. At this point you may very well say something to yourself along the lines of: 'one does not count the hours when one is in love'.

3. What are the regulations around bees in the city?

Laws surrounding beekeeping vary dramatically by municipality or province / state. See the bottom of this page for Canadian info. This Forum thread contains links to regulations for many American states.

Photo by:edibleoffice

In some cities beekeeping may not be permitted at all, while other cities may require such things as: limits to your hive numbers, meeting specific hive distance or position criteria, taking some form of training, registering your hives, and following certain management practices.

Generally, the intentions behind these regulations fall into one or both of two groups:

a) To protect other beekeepers from the spread of pests and disease.

b) To protect the public from safety risks.

You will likely find it upsetting if you discover that your municipality is less permissive than some other urban areas. The laws in your area may very well be unreasonable, but keep in mind that your fellow neighbours and beekeepers really do deserve some level of real respect. I keep bees in Toronto, where provincial regulations specifying that hives be placed 30 m from property lines make it impossible to keep bees legally in your backyard. Nevertheless, a fairly large contingent of us have been creative in finding suitable, legally compliant sites.

In my context, I have little interest in breaking the law for bees - I'd worry my beekeepers liability insurance would not be honoured if I kept illegal hives, and I feel it's probably better to give bees some space anyway, so I'm happy to go a little out of my way for the privilege of keeping bees.

4. I've never kept bees before, how do I learn?

Beekeeping where there may be only a small buffer zone between other people and an unexpected bee problem means beekeeping with raised stakes. Knowing as much as possible about what you can expect in different situations before setting up your own urban hives will go a long way in reducing your stress levels and reducing the risks involved with keeping bees.

Photo by: Meg Riordan

There's no substitute for first hand experience. As a beekeeper’s focus and activities can vary a fair bit at different points in the season, courses that bring you into the bee yard at different times of the year are preferable to more intensive workshops that try to cover everything in a single day or weekend.

Local beekeepers’ associations are fairly common around the world. Attending their meetings is an excellent way to meet other beekeepers who might enjoy some help around their hives and be willing to mentor you.

Do still read as much as you can. Ideas on how to do things vary wildly among beekeepers, and in some cases different resources will outright contradict each other on what would appear to be statements of fact rather than personal preference. As they can't all be right... well, at least not all of the time… familiarizing yourself with some of the different schools of thought may equip you with a broader ability to interpret what is actually happening with your own bees. For this same reason, I recommend seeking out the more in depth resources right from the start, rather than looking at the 'quick starter guide' style of resources.

5. Will a backyard hive impact my neighbours?

On an emotional level, the presence of a beehive tends to elicit a strong response. Some will be excited and think you're amazing, while others will be terrified and think you're insane; only rarely will people be completely indifferent.

Photo by: Tim Tuttle

There's somewhat of a divide in opinion as to whether or not to tell your neighbours about your new hobby. Some will argue that you should attempt to be stealthy and subtle lest some mean spirited or overly paranoid neighbour starts making things difficult for you. On the other hand, I would suggest that there might be some advantages to being up front about your plan, as there is a good likelihood that the people around you will, sooner or later, notice the sudden propensity towards white jumps suits and veils in your fashion selections and the 80,000+ bees that are being sheltered a few feet away from their family home.

Photo by:WoK111

There's been a great deal written about the gentle, docile nature of the honeybee. For the most part I agree, bees are primarily interested in flowers and have little time for picking unnecessary fights with people while away from the hive.

I'm often able to sit peacefully beside my unopened hives without any protective equipment. At 10-20 feet, without a direct line of vision to a hive, it can be difficult for your average person to even notice that bees are flying around them. This, however, does not mean beekeeping is a risk free activity. There are a few situations that will come up that can change the mood of your bees, as well as increase the potential for a negative encounter between human and bee. Examples of such situations include: a nectar dearth that necessitates that you feed your bees, some methods of honey harvesting, allowing a colony to swarm, or an accidental dropping of a frame or a box full of bees.